1972 U.S. Embassy proposal to review U.S.-Japan Joint Committee framework blocked by military

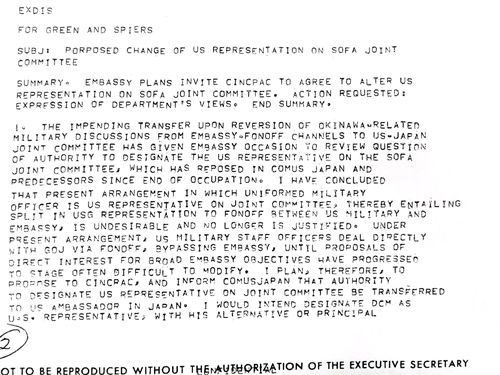

Confidential telegram from U.S. Embassy in Japan to the Department of State, recommending that U.S. representation on the U.S.-Japan Joint Committee change over to the Embassy on occasion of Okinawan reversion to Japanese sovereignty.

January 3, 2018 Ryukyu Shimpo

By Washington Special Correspondent Yukiyo Zaha and Ryota Shimabukuro

It recently came to light through declassified official U.S. documents that in May 1972, with the reversion of Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty posing a turning point, the U.S. Embassy in Japan proposed a review of the framework of the U.S.-Japan Joint Committee.

The Embassy was concerned about the existence of this unusual relationship built to function during the occupation period. This Joint Committee is a mechanism for discussion of U.S. military stationing in Japan established through the U.S.-Japan Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA).

The Department of State supported the Embassy’s proposal, but met with resistance from the U.S. military. So, the framework wherein military authorities headed the U.S. representation of the Committee was retained.

The Embassy’s proposal asked for changes to the framework in which the Deputy Commander of the U.S. Forces, Japan (USFJ) acts as representative of the Committee.

Because civilians account for all Japanese representation on the Committee, the proposal also suggested that U.S. representation be switched to Embassy diplomats, and that the U.S. military assist the Embassy from a technical perspective.

For the first time on the Joint Committee, currently five of the six U.S. committee representatives are military personnel.

Although it has been pointed out that military concerns take top priority in consultations between the U.S. and Japan, now criticism that the U.S. government’s inner operations are military-led is on the rise as well.

A July 31, 2002 command policy by the USFJ specified that, “The U.S. Representative [the Deputy Commander of the USFJ] is not solely a representative of U.S. Forces, Department of Defense, Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps. He is a representative of the US Government.”

Furthermore it set out that, “The only person authorized to speak or to act for the U.S. in the Joint Committee is the U.S. Representative, or in his absence, the Senior or Alternate U.S. Deputy Representative.”

This policy demonstrates that even now the U.S. military holds great power on the Joint Committee.

In May 1972, U.S. Ambassador to Japan Robert Ingersoll sent a confidential telegram addressed to the Department of State expressing dissatisfaction with designation of Joint Committee U.S. representatives and proposing a review of this process.

It stated that discussions related to the reversion of Okinawa gave the Embassy occasion to review the question of the authority to designate U.S. representation on the SOFA Joint Committee.

It also pointed out that under the arrangement of the time, the U.S. military staff officials would deal directly with the Japanese government, bypassing the U.S. Embassy.

The Department of State replied in agreement to Ingersoll’s message, expressing that the Joint Committee framework is not consistent with arrangements in many other countries, and that considering the circumstances in Japan at the time this framework could no longer be justified.

However, the U.S. Pacific Fleet and USFJ resisted, arguing that it was important for the military to preserve its flexibility and responsiveness.

They also insisted that the Joint Committee functioned well, and there was no indication of Japanese officials requesting a change.

These arguments were sent to the U.S. Embassy in a telegram in June 1972.

In the same month the Embassy issued a document criticizing the Joint Committee framework and the unusual relationship built for the occupation period, in which Japanese civilian representatives directly discuss with U.S. military representatives.

In addition, since the security relationship with Japan has come to be affected by economic and political factors, the telegram contained a request for representative authority to be transferred to the U.S. Embassy.

However, an official document issued by the U.S. Embassy in August 1972 sets forth the series of events through which negotiations between the Embassy and the U.S. military ultimately concluded in a decision to modify operation internally on the U.S. side of the Committee, with the changes involving appointment of a diplomat from the Embassy as a representative agent, subordinate to the Deputy Commander of the USFJ, and timely provision by the U.S. military to the Embassy of information regarding politically sensitive issues.

The telegram from the U.S. Embassy in Japan is held in the National Archives.

(English translation by T&CT and Erin Jones)

Previous Article:Another MCAS Futenma helicopter emergency landing, this time in Yomitan Village

Next Article:Shimoji of Kinoshita Circus thrills the audience

[Similar Articles]

- U.S. military has not required pre-departure PCR testing for servicemembers coming to bases in Japan since September, has permitted movement between Bases During Periods of Activity Restrictions

- Joint statement does not touch upon Futenma relocation issue

- U.S. military disposes of 2017 helicopter fire incident soil without notifying Japanese authorities

- In year-opening statement, Governor Tamaki plans to release a proposal for the 50th anniversary of the reversion “taking into account the opinions of Okinawan residents,” resolves to reduce the burden of U.S. military bases

- U.S. Senate panel rejects budget for transferring Marines stationed in Okinawa to Guam

Webcam(Kokusai Street)

Webcam(Kokusai Street)