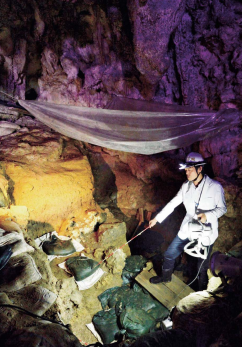

Excavated fishhooks show that Paleolithic people fished, ate well

Masaki Fujita of the Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum shows the location where fish hooks from roughly 23,000 years ago were discovered at the Valley of Gangara in Nanjo, Okinawa

September 20, 2016 Ryukyu Shimpo

At the Sakitari cave (survey site 1) in Nanjo, Okinawa where the world’s oldest fishhooks were unearthed, other artifacts including roughly 10,000 Japanese mitten crab claws were also found. The Japanese mitten crab is related to the Chinese mitten crab, which is known as a delicacy. Many giant mottled eel bones, “irabucha” (knobsnout parrotfish) bones and other fish bones were also found. Knobsnout parrotfish is known to be delicious eaten raw as sashimi. It has been said that it was likely difficult to live long-term in an island environment like Okinawa with limited resources, but these discoveries show that humans made a living through fishing for more than 20,000 years. Masaki Fujita of the Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum, a specialist in physical anthropology, who was in charge of the survey, says that people then appear to have led a surprisingly gourmet lifestyle.

Judging from the size of the excavated crab claws, the crabs’ shells were likely 8 centimeters wide. This is the size of the crabs when they are at their largest, right before they lay their eggs in autumn. After the eggs hatch in the ocean, the baby crabs grow as they swim up the river, then head toward the ocean to spawn. Fujita surmises that ancient fishermen aimed to catch the crabs right at the season when they were fullest with meat and innards.

Because the size of the crabs alone does not provide strong enough evidence, the survey also focused on “kawanina” freshwater snails that were excavated at the same time. The proportion of oxygen isotopes in the snail shells changes in accordance with increases and decreases in water temperature. By analyzing the shells, it is possible to estimate the season in which they died—that is, in which they were caught and eaten. An analysis of the excavated snail shells showed that of 28 shells for which data reflecting a season was obtained, 19 were caught in autumn, eight in summer, and one in winter.

“The Japanese mitten crab is nocturnal, so people would have come to live in this cave every autumn, caught crabs and snails at night, and eaten them,” said Fujita, appearing confident in his hypothesis.

Until now, the oldest known fishhooks were ones made of shells discovered at the Jerimalai site in East Timor. They were estimated to be between 16,000 and 23,000 years old, but the exact date was unspecified. In Japan, the oldest known fishhooks were ones uncovered at Natsushima Kaizuka in Yokosuka, Kanagawa, which are estimated to be from the Jomon era, between 9,000 to 10,000 years old. There was previously no material suggesting that people were engaged in fishing in the Paleolithic era.

“Now when we imagine the lives of Paleolithic people, we can also imagine them enjoying fishing by the ocean or river. They could have eaten the same things we ate today and enjoyed the same delicious taste,” Fujita said with a smile.

Terms: Paleolithic era and calibrated age

In Japan, the Jomon period, called the Kaizuka period in Okinawa, began 16,000 years ago during the Neolithic era. The time before the Neolithic era was the Paleolithic era, which is known in Japan as the Preceramic period. Radiocarbon dating is used to estimate the age of artifacts from the Paleolithic era, and a calibrated age is now also displayed, being estimated by correcting the age obtained by radiocarbon dating using methods such as verifying the growth rings of plants. The calibrated age is a larger number than the age obtained using radiocarbon dating, and is closer to the actual age of the artifact.

(English translation by T&CT and Sandi Aritza)

Previous Article:World’s oldest fishing hooks from 23,000 years ago discovered in Sakitari Cave in Okinawa

Next Article:Okinawa appeals Henoko ruling; final decision expected by year’s end

[Similar Articles]

- World’s oldest fishing hooks from 23,000 years ago discovered in Sakitari Cave in Okinawa

- Japan’s oldest shell tools found in Sakitari Cave in Okinawa

- Quartz fragments and human remains excavated at Sakitari Cave, Tamagusuku, Nanjo City

- Crabs come out at night under the light of the moon to lay eggs on Miyagi Island

- 9,000-10,000-year-old bone fragments discovered in Okinawa thought to be missing link between Paleolithic and Kaizuka-era humans

Webcam(Kokusai Street)

Webcam(Kokusai Street)